Computational Thinking

Contents

Computational Thinking 1#

Finding the one definition of Computational Thinking (CT) is a task doomed to failure, mainly because it is hard to have a consensus on what CT means to everyone. To ease the communication and have a shared meaning, we consider CT as an approach to “solve problems using computers as tools” (Beecher, 2017). Notice that CT is not exclusively considered in computer science. On the contrary, CT impacts a wide range of subject areas such as mathematics, engineering, and science in general.

There is a misunderstanding regarding the relationship between CT, computer science, and programming. Some people use them interchangeably, but the three terms are not equivalent. Computer science aims at building and understanding the principles of mathematical computation; while programming–which happens to be a subfield of computer science–focuses on high-quality program writing. Although the three terms are related and might intersect in many points, CT should be seen as a method of problem-solving that is frequently (but not exclusively) used in programming. In essence, problem-solving is a creative process.

Some of the core concepts behind CT are:

Logic

Algorithms

Decomposition

Abstraction

Generalization

Modeling

Hereafter, we will explore what these concepts mean and how they can help you when solving a problem.

Computational thinking

Computational thinking is an approach to problem-solving that involves using a set of practices and principles from computer science to formulate a solution that’s executable by a computer. [Bee07]

Logic #

Logic is the study of the formal principles of reasoning. These principles determine what can be considered a correct or incorrect argument. An argument is “a change of reasoning that ends up in a conclusion” [Bee07]. Every statement within an argument is called a proposition, and it has a truth value. That is, it is either true or false. Thus, certain expressions like questions (e.g. “are you hungry?”) or commands (e.g. “clean your bedroom!”) cannot be propositions given that they do not have a truth value.

Below we present a very famous argument in the logic field:

Socrates is a man.

All men are mortal.

Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

This argument is composed of three propositions (each one is enumerated). These statements are propositions because all of them have a truth value. However, you can notice that some of these statements are used to arrive at a conclusion. The propositions that form the basis of an argument are known as premises. In our example, propositions 1 and 2 are premises. Lastly, the proposition that is derived from a set of premises is known as a conclusion.

Logic

Logic studies the formal principles of reasoning, which determine if an argument is correct or not. An argument is a sequence of premises. Each premise is a statement that has a truth value (i.e. true or false).

Types of Arguments#

Arguments can either be deductive or inductive.

Deductive Arguments#

Deductive arguments are considered a strong form of reasoning because the conclusion is derived from previous premises. However, deductive arguments can fail in two different scenarios:

False premises: One of the premises turns to be false. For example:

I eat healthy food.

Every person eating healthy food is tall.

I am tall.

In this example, premise 2 is false. It is not true that every person eating healthy food is tall. Then, this argument fails.

Faulty logic: The conclusion is wrongly derived out from the premises. For example:

All bitterballen are round.

The moon is round.

The moon is a bitterbal.

In this case, the conclusion presented in premise 3 is false. It is true that bitterballen are round and that the moon is round, but this does not imply that the moon is a bitterbal! By the way, a “bitterbal” is a typical Dutch snack, to be eaten with a good glass of beer!

Inductive Arguments#

Although deductive arguments are strong, they follow very stern standards that make them difficult to build. Additionally, the real world usually cannot be seen just in black and white–there are many shades in between. This is where inductive arguments play an important role. Inductive arguments do not have an unquestionable truth value. Instead, they deal with probabilities to express the level of confidence in them. Thus, the conclusion of the argument cannot be guaranteed to be true, but you can have a certain confidence in it. An example of an inductive argument comes as follows:

Every time I go out home it is raining.

Tomorrow I will go out from home.

Tomorrow it will be raining.

There is no way you can be certain that tomorrow will rain, but given the evidence, there is a high chance that it will be the case. (The chance might be even higher if we mention that we are living in the Netherlands!)

Deductive and inductive arguments

Arguments can be either deductive or inductive. On the one hand, deductive arguments have premises that have a clear truth value. On the other hand, inductive arguments have premises associated with a level of confidence in them.

Boolean Logic#

Given their binary nature, computers are well suited to deal with deductive reasoning (rather than inductive). To allow them to reason about the correctness of an argument, we use Boolean logic. Boolean logic is a form of logic that deals with deductive arguments–that is, arguments having propositions with a truth value that is either true or false. Boolean logic or Boolean algebra was introduced by George Boole (that is why it is called Boolean) in his book “The Mathematical Analysis of Logic” in 1847. It deals with binary variables (with true or false values) representing propositions and logical operations on them.

Logical Operators#

The main logical operators used in Boolean logic to connect propositions are:

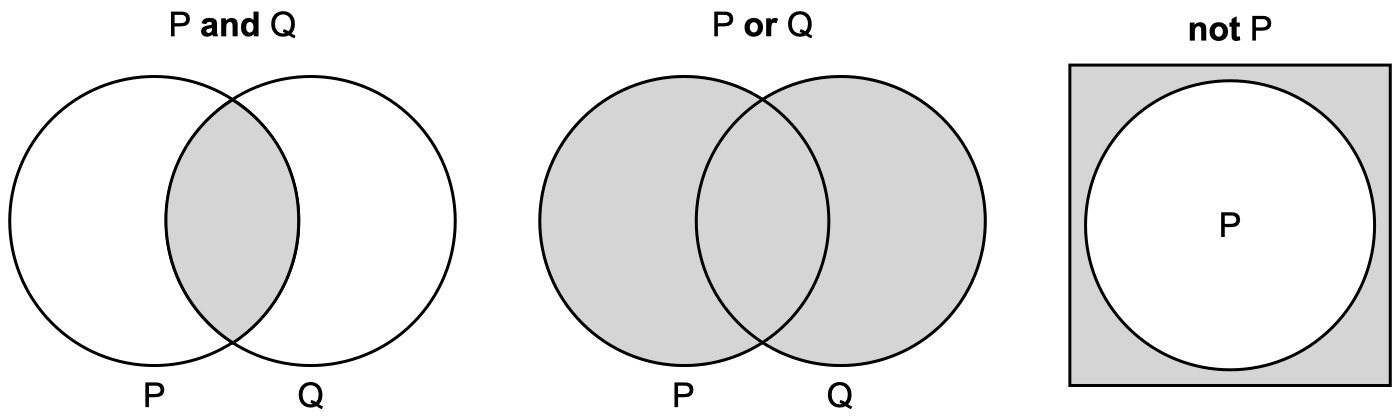

And operator: It is also known as the conjunction operator. It chains premises in such a way that all of them must be true for the conclusion to be true.

Or operator: It is also known as the disjunction operator. It connects premises in such a way that at least one of them must be true for the conclusion to be true.

Not operator: It is also known as the negation operator. It modifies the value of a proposition by flipping its truth value.

In Boolean logic, propositions are usually represented as letters or variables (see previous figure). For instance, going back to our Socrates argument, we can represent the three propositions as follows:

P: Socrates is a man.

Q: All men are mortal.

R: Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

In order for R to be true, P and Q most be true.

We can now translate this reasoning into Python. To do that use the following table and execute the cell below.

Operator |

Technical name |

Symbol |

Python |

|---|---|---|---|

And |

Conjunction |

\(\land\) |

|

Or |

Disjunction |

\(\lor\) |

|

Not |

Negation |

\(\lnot\) |

|

# Change the truth values of p and q to see how the conclusion r changes

p = True

q = True

r: bool

if p and q:

r = True

else:

r = False

print(r)

True

The previous translation to Python code of the deductive argument is correct, however we can do way better! Let us see:

# Change the truth values of p and q to see how the conclusion r changes

p = True

q = True

r = p and q

print(r)

True

Sometimes conditionals are not really needed; using a Boolean expression as the one shown above is sufficient. Having unneeded language constructs (e.g. conditionals) can negatively impact the readability of your code.

Algorithms #

We can use logic to solve everyday life problems. To do so, we rely on the so-called algorithms. Logic and algorithms are not equivalent. On the contrary, an algorithm uses logic to make decisions for it to solve a well-defined problem. In short, an algorithm is a finite sequence of well-defined instructions that are used to provide a solution to a problem. According to this definition, it seems that algorithms are what we create, refine, and execute every single day of our lives, isn’t it? Think for instance about the algorithm to dress up in the morning or the algorithm (or sequence of steps) that you follow to bake a cake or cook a specific recipe. Those are also algorithms that we have internalized and follow unconsciously.

To design an algorithm, we usually first need to specify the following set of elements:

the problem to be solved or question to be answered. If you do not have a well-defined problem you might end up designing a very efficient but useless algorithm that does not solve the problem at hand. Thus, ensure you understand the problem before thinking about a solution;

the inputs of the algorithm–that is, the data you require to compute the solution;

the output of the algorithm–that is, the expected data that you want to get out from your solution, and;

the algorithm or sequence of steps that you will follow to come up with an answer.

Without having a clear picture of your problem, and the expected inputs and output to solve that problem, it will be unlikely that you will be able to come up with a proper algorithm. Furthermore, beware that for algorithms to be useful, they should terminate at some point (they cannot just run forever without providing a solution!) and output a correct result. An algorithm is correct if it outputs the right solution to every possible input. Proving this might be unfeasible, which is why testing your algorithm (maybe after implementing a program) is crucial.

Algorithm

An algorithm is a finite sequence of clearly defined instructions used to solve a specific problem.

Appeltaart Algorithm#

To be conscious about the process of designing an algorithm, let us create an algorithm to prepare the famous Dutch Appeltaart. The recipe has been taken from the Heel Holland Bakt website.

Problem#

We will start by defining the problem we want to solve. In our case, we want to prepare a classical Dutch Appeltaart.

Inputs (Ingredients)#

The inputs to our algorithm correspond to the ingredients needed to prepare the pie. We list them below:

Dough

200 grams of butter

160 grams of brown sugar

0.50 teaspoon of cinnamon

300 grams of white flour

a pinch of salt

1 egg

breadcrumbs

Apple filling

100 grams of raisins

rum

8 apples

100 grams of shelled walnuts

5 tablespoons of sugar

3 teaspoons of cinnamon

Decoration

1 egg for brushing

25 white almonds

Output (Dish)#

The expected output of our algorithm is a delicious and well-prepared Dutch Appeltaart.

Algorithm (Recipe)#

Preparation

Grease a round pan and dust with flour.

Preheat the oven to 180°C.

Dough

- Mix the butter with brown sugar and cinnamon.

- Add the flour with a pinch of salt to the butter mixture.

- Add 1 egg to the mixture.

- Knead into a smooth dough and let rest in the fridge for at least 15 minutes.

- Roll out 2/3 of the dough and line the pan with it.

- Spread the breadcrumbs over the bottom.

- Place the pan in the fridge to rest.

Apple filling

- Put the raisins in some rum.

- Peel the apples and cut them into wedges.

- Strain the raisins.

- Mix the apples with raisins, walnuts, sugar, and cinnamon.

Decoration

- Pour the filling into the pan.

- Cover the top of the pie with the remaining dough.

- Brush the top with a beaten egg and sprinkle with the almonds.

- Bake the apple pie for about 60 minutes.

- Let cool and enjoy!

Language#

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” - Ludwig Wittgenstein

In the previous section, we were able to write down the algorithm to prepare a Dutch Appeltaart. Writing down an algorithm is of great importance given that you do not only guarantee that you can execute the algorithm in future opportunities, but you also provide a means to share the algorithm, so other people can benefit from what you designed. But to be able to write down the algorithm, we require an additional tool–that is, a language. In the previous example, we used English to describe our Appeltaart algorithm. However, if you remember correctly, computational thinking relies on computers to solve real-world problems. Thus, the algorithms we want to write down must be written in a language that can be understood by a computer. But beware! The computer is not the only other entity that needs to understand your algorithm: what you write down should be understood by both the machine and other people that might read it afterward (including the you from the future).

Language is a system of communication. It has a syntax and semantics:

The syntax of a language describes the form or structure of the language constructs. The syntax can be defined with a grammar, which is a set of rules that specify how to build a correct sentence in the language.

The semantics describes the meaning of language constructs.

Languages can also be classified as natural or formal:

Natural languages are languages used by people to communicate with each other (e.g. English, Spanish, Dutch, Arabic). They were not designed from the very beginning, on the contrary, they evolved naturally over time.

Formal languages are languages designed by humans for specific domains or purposes. They usually are simplified models of natural language. Examples of formal languages are the mathematical, chemical, or staff (standard music notation) notations. There is also a very important example that interests us the most: programming languages.

Programming Languages#

Programming languages are formal languages with very strict syntax and semantics. These languages are used to write down algorithms. A program is, then, an algorithm implemented using a programming language. To this point, we can make some connections with previous concepts: CT is a method of problem-solving where problems are solved by reusing or designing a new algorithm. This algorithm might later be written down as a program to compute a solution to the original problem.

Python is an example of a programming language. It was conceptualized in 1989 by Guido van Rossum when working at the Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica (CWI), in Amsterdam. Python saw its beginnings in the ABC language. Its name–referring to this monumental sort of snake–actually comes from an old BBC series called Monty Python’s Flying Circus. Guido was reading the scripts of the series and he found out that Python sounded “short, unique, and slightly mysterious”, which is why he decided to adopt the name.

Please clarify that there is a difference between solving a problem, inventing an algorithm, and writing a program.

It maybe the case that to solve a problem you apply a known algorithm, think of sorting words, but it may also be the case that to solve the problem you have to come up with a new algorithm.

The Zen of Python#

In 1999, Tim Peters–one of Python’s main contributors– wrote a collection of 19 principles that influence the design of the Python programming language. This collection is now known as the Zen of Python. Peters mentioned that the 20\(^{th}\) principle is meant to be filled in by Guido in the years to come. Have a look at the principles. You can consider them as guidelines for the construction of your own programs.

Beautiful is better than ugly.

Explicit is better than implicit.

Simple is better than complex.

Complex is better than complicated.

Flat is better than nested.

Sparse is better than dense.

Readability counts.

Special cases aren't special enough to break the rules.

Although practicality beats purity.

Errors should never pass silently.

Unless explicitly silenced.

In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess.

There should be one -- and preferably only one -- obvious way to do it.

Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you're Dutch.

Now is better than never.

Although never is often better than *right* now.

If the implementation is hard to explain, it's a bad idea.

If the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea.

Namespaces are one honking great idea -- let's do more of those!

Language

A language is a system of communication, that has syntax and semantics. The syntax describes the form of the language, while the semantics describes its meaning. A language can be either natural (evolves naturally) or formal (designed for a specific domain or purpose). Programming languages are a sort of formal languages and are used to allow communication between humans and computers.

Decomposition #

In 1945 (in the year that the II World War ended), George Pólya, a Hungarian mathematician, wrote a book called “How to Solve It”. The book presents a systematic method of problem-solving that is still relevant today. In particular, he introduced problem-solving techniques known as heuristics. A heuristic is a strategy to solve a specific problem by yielding a good enough solution, but not necessarily an optimal one. There is one important type of heuristic known as decomposition. Decomposition is a divide-and-conquer approach that breaks complex problems into smaller and simpler subproblems, so we can deal with them more efficiently.

In programming, we have diverse constructs that will ease the implementation of decomposition. In particular, classes and functions (or methods) are a means to divide a complex solution to a complex problem into smaller chunks of code. We will cover these topics later in the course.

Decomposition

Decomposition is a divide-and-conquer approach that breaks complex problems into smaller and simpler subproblems.

Abstraction & Generalization #

Abstraction is the process of hiding irrelevant details in a given context and preserving only the important information. Abstraction is required when generalizing. In fact, generalization is the process of defining general concepts by abstracting common properties from a set of instances. In other words, generalization allows you to formulate a unique concept out of similar but not necessarily identical entities. When generalizing a solution, it becomes simpler because there are fewer concepts to deal with. The solution also becomes more powerful in the sense that it can be applied to more problems of similar nature.

To be able to generalize a solution or algorithm, you need to start developing your ability to recognize patterns. For instance:

A sequence of instructions that are repeating multiple times can be generalized into loops.

Specialized instructions that are employed more than once in different scenarios can be encapsulated in subroutines or functions.

Constraints that determine the flow of execution of your algorithm can be generalized in conditionals.

Abstraction and generalization

Abstraction is the process of preserving relevant information in a given context and hiding irrelevant details. In addition, generalization is the process of defining general concepts by abstracting common properties from a set of instances.

Modelling #

All models are wrong, but some are useful. (Box, 1987)

Humans and computers are not able to completely grasp and understand the real world. Thus, to solve real-world problems, we usually need to create models that help us understand and solve the issue. A model is a representation of an entity. Thus, a model as a representation that, by definition, ignores certain details of the represented entity, is also a type of abstraction. A model in computer science usually consists of:

Entities: core concepts of the represented system.

Relationships: connections among entities within the represented system.

Models usually come in two flavors:

Static models: these models reflect a snapshot of the system at a given moment in time. The state of the system might change in the future but the changes are so small or unfrequent that the model is still useful and sufficient.

Dynamic models: these models explain changes in the state of a system over time. They always involve states (description of the system at a given point in time) and transitions (state changes). Some dynamic models can be executed to predict the state of the system in the future.

When creating a model you should verify that:

The model is useful to solve the problem at hand.

You are strictly following the rules, notation, and conventions to define a model.

The level of accuracy of your model is acceptable to solve the problem (i.e. you keep the strictly needed information).

You have defined the level of precision at which you represent your model (especially when dealing with decimal numbers; how many decimal points are required?).

Model

A model is a representation of an entity. It is a type of abstraction.

Example: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland #

In this section, we will apply computational thinking to solve a problem from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, written by Lewis Caroll. In chapter I, “Down the Rabbit Hole”, Alice found herself falling down into a rabbit hole. She finally reached the ground, coming upon “a heap of sticks and dry leaves”. Alice found herself in a “long, low hall, which was lit up by a row of lamps hanging from the roof”.

“There were doors all around the hall, but they were all locked”. She started “wondering how she was ever to get out again”. She suddenly discovered a tiny golden key on a little three-legged table, all made of solid glass. After looking around, “she came upon a low curtain she had not noticed before, and behind it was a little door about fifteen inches high: she tried the little golden key in the lock, and to her great delight it fitted!” But she was not able to go through it; the doorway was too small.

Later in the chapter, we find out that there was a bottle with a ‘DRINK ME’ label that makes shorter anyone drinking its content. There was also a very small cake with the words ‘EAT ME’ beautifully marked in currant. Anyone eating the cake will grow larger. How can we help Alice go out of the hall through the small doorway behind the curtain?

To solve this problem, assume that:

Alice is 60 inches tall;

Alice can go out of the doorway if she is taller than 10 inches (exclusive) and shorter than 15 inches (inclusive);

one sip of the ‘DRINK ME’ bottle makes anyone get 11 inches shorter;

Alice can only sip from the bottle at a point in time;

one bite of the ‘EAT ME’ cake makes anyone grow 1 inch larger;

Alice can only have a bite of the cake at a point in time, and;

Alice cannot sip from the bottle and a bite of the cake at the same time.

Understanding the Problem#

Problem: Alice wants to go out of the hall. To do so, she needs to go through the doorway behind the curtain, but she is too tall to go through it.

Identifying the Inputs#

The inputs we have at hand are:

Alice’s height (i.e. 60 inches)

Doorway height (i.e. 15 inches)

Height decrease after taking a sip from the ‘DRINK ME’ bottle (i.e. 11 inches)

Height increase after taking a bite from the ‘EAT ME’ cake (i.e. 1 inch)

alice = 60 # Alice's height

max_doorway = 15 # Max doorway height

min_doorway = 10 # Min doorway height

drink = 11 # Height decrease after taking a sip from the 'DRINK ME' bottle

eat = 1 # Height increase after taking a bite from the 'EAT ME' cake

Note that:

We abstracted the relevant information to the problem. Details are removed if they are not needed;

thus, the inputs are useful to solve the problem.

The inputs were written in Python. They follow the syntax rules of the programming language.

The identified inputs are enough to accurately solve the problem.

We use integers to represent Alice’s height. There is no need to use floats. Therefore, the level of precision of our model is acceptable to solve the problem.

Identifying the Expected Output#

As a solution to our problem, we want Alice to go out from the hall through the doorway. To do so, her height should be greater than 10 inches and less than or equal to 15 inches.

Output: Alice’s height should be greater than 10 inches and less than or equal to 15 inches.

Designing the Algorithm#

To solve the problem we know that:

Alice must go out from the hall through the doorway if she is larger than 10 inches and shorter or exactly 15 inches.

Alice must drink out from the ‘DRINK ME’ bottle if she is taller than 15 inches–that is, she will shorten 11 inches.

Alice must bite the ‘EAT ME’ cake if she is shorter or exactly 10 inches–that is, she will grow 1 inch.

Steps 2 and 3 shall be repeated until she can to go out from the hall.

Note that:

We decomposed the problem of getting the right height into two subproblems: making Alice get larger and making Alice get shorter.

We generalized our solution by identifying patterns in our algorithm (e.g. step 4).

Now, we will implement our algorithm in Python.

# Inputs

alice = 60 # Alice's height

max_doorway = 15 # Max doorway height

min_doorway = 10 # Min doorway height

drink = 11 # Height decrease after taking a sip from the 'DRINK ME' bottle

eat = 1 # Height increase after taking a bite from the 'EAT ME' cake

# Algorithm

while True:

if 10 < alice <= 15:

print('Alice is ' + str(alice) + ' inches. She can go out of the hall through the doorway!')

break

elif alice < 10:

print('Alice is ' + str(alice) + ' inches. Take a bite from the "EAT ME" cake!')

alice = alice + eat

elif alice > 15:

print('Alice is ' + str(alice) + ' inches. Take a sip from the "DRINK ME" bottle!')

alice = alice - drink

# Output

print(alice)

Alice is 60 inches. Take a sip from the "DRINK ME" bottle!

Alice is 49 inches. Take a sip from the "DRINK ME" bottle!

Alice is 38 inches. Take a sip from the "DRINK ME" bottle!

Alice is 27 inches. Take a sip from the "DRINK ME" bottle!

Alice is 16 inches. Take a sip from the "DRINK ME" bottle!

Alice is 5 inches. Take a bite from the "EAT ME" cake!

Alice is 6 inches. Take a bite from the "EAT ME" cake!

Alice is 7 inches. Take a bite from the "EAT ME" cake!

Alice is 8 inches. Take a bite from the "EAT ME" cake!

Alice is 9 inches. Take a bite from the "EAT ME" cake!

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

KeyboardInterrupt Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[4], line 17

15 print('Alice is ' + str(alice) + ' inches. Take a bite from the "EAT ME" cake!')

16 alice = alice + eat

---> 17 elif alice > 15:

18 print('Alice is ' + str(alice) + ' inches. Take a sip from the "DRINK ME" bottle!')

19 alice = alice - drink

KeyboardInterrupt:

Let us try to improve our previous algorithm. We can always make it more beautiful, more explicit, simpler, and more readable. Remember that “if the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea” (see the Zen of Python).

Note: In the following code, we will use f-Strings. We will talk more about later in the course, but now you can start grasping what is their use and how we can build them.

# Inputs

alice = 60 # Alice's height

max_doorway = 15 # Max doorway height

min_doorway = 10 # Min doorway height

drink = 11 # Height decrease after taking a sip from the 'DRINK ME' bottle

eat = 1 # Height increase after taking a bite from the 'EAT ME' cake

# Algorithm

while alice < min_doorway or alice >= max_doorway:

if alice < min_doorway:

print(f'Alice is {alice} inches. Take a bite from the "EAT ME" cake!')

alice += eat

else:

print(f'Alice is {alice} inches. Take a sip from the "DRINK ME" bottle!')

alice -= drink

print(f'Alice is {alice} inches. She can go out of the hall through the doorway!')

# Output

print(alice)

Well done! We have applied computational thinking to design a solution to Alice’s problem.

(c) 2021, Lina Ochoa Venegas, Eindhoven University of Technology